The folk crafts of Mexico, called artesanía, form a bright, living mix of many cultures over many centuries. They are more than decoration; they show Mexico’s history, beliefs, and daily life. From playful alebrijes to the fine patterns of Huichol art, Mexican folk crafts show lasting creativity and skill. They blend Indigenous roots with European methods and attract people at home and abroad.

What Are Folk Crafts of Mexico?

How Are Folk Crafts Defined in the Mexican Context?

In Mexico, artesanía is a wide group of handmade items that covers useful objects and fine folk art. This shared label points to common history and cultural meaning. Unlike factory goods, artesanía comes from everyday people-often in rural areas-who use methods taught in their families. Many pieces are practical, like cooking pots and clothing, yet decoration, bright color, and clever design turn them into art.

The word artesanía took hold in the 20th century to set these handmade pieces apart from industrial products. People value the human touch, learned skills, and the stories inside each item. Whether an embroidered shawl or a finely painted vase, artesanía keeps a link to the past and celebrates cultural heritage.

What Sets Mexican Folk Crafts Apart from Other Traditional Arts?

Mexican folk crafts stand out for their mixed “mestizo” character-a blend of Indigenous and European ideas that has grown for 500 years. The Spanish arrival in 1521 brought new tools, materials, and styles, which joined with existing local work.

- Blended methods: potter’s wheel and glazing joined older pottery; saddlemaking with Indigenous designs became local craft.

- Strong color: from ancient times, makers used ochre red, bright green, burnt orange, yellow, and turquoise; later contacts added more hues.

- Rich detail: many pieces favor curved lines and heavy ornament, shaped by Spanish colonial taste and older traditions.

How Have Folk Crafts Shaped Mexican History and Culture?

Origins of Mexican Folk Crafts

Mexican craft roots go back to Mesoamerica long before Spain. As early as 1500 BCE, great cultures grew and made skilled work.

- Olmec

- Maya

- Teotihuacán

- Toltec

- Aztec

People wove, carved wood, and made pottery for daily life and important ceremonies. Crafts helped share feelings and social ties, such as:

- expressing hopes and fears,

- courtship and play,

- honoring gods and ancestors.

By the late pre-Conquest era, the Aztec Empire drew on Toltec, Mixtec, Zapotec, and Maya skills. Reports by Hernán Cortés describe busy markets in Tenochtitlan with textiles, feather art, gourd vessels, and precious metal pieces. Bernardino de Sahagún wrote about many uses of the maguey plant and many types of pottery, and he noted that artisans held high status.

Influence of Indigenous, Colonial, and Modern Traditions

The 1521 Conquest changed craft making. Early on, many native makers faced pressure because some designs were tied to banned religious practices. Yet missions taught new European crafts and methods, and surviving trades-like pottery-gained the wheel and glaze. New work like saddlemaking took root with Indigenous motifs.

Key figures helped rebuild crafts. Vasco de Quiroga in Michoacán mixed native and Spanish methods and urged towns to specialize to reduce rivalry. Near the end of the colonial period, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla promoted crafts to help lower classes, setting up workshops and training. He faced pushback, but his efforts led to Majolica pottery in Guanajuato. After the Revolution, artists and thinkers lifted folk art as a core part of national identity. Old practices, colonial changes, and modern ideas together shaped today’s lively craft scene.

What Types of Folk Crafts Are Most Prominent in Mexico?

Huichol Art

Huichol art comes from the Sierra Madre Occidental in Jalisco and Nayarit. Indigenous Huichol artists press tiny beads or colored yarn onto boards with wax and resin to make detailed designs. These patterns have deep meaning. Many reflect visions linked to peyote rites, central to Huichol belief. Common forms include jewelry, bowls, and yarn pictures of animals like jaguars and wolves.

Each color and symbol tells part of a story passed down through families. The careful, time-heavy process-thousands of beads or strands of yarn-shows strong dedication and spiritual focus.

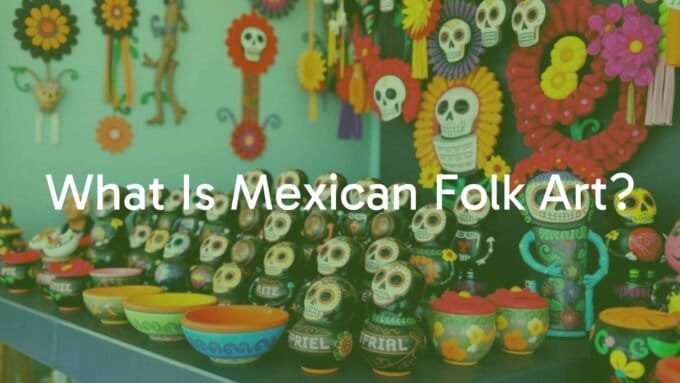

Alebrijes and Woodcarving

Alebrijes are bright, fantasy creatures built from parts of different animals. In 1936, Pedro Linares López, a cardboard artisan in Mexico City, became very ill and dreamed of strange animals saying “alebrije.” After he recovered, he made them in cardboard and painted them in lively colors.

Later, in San Martín Tilcajete, Oaxaca, makers began carving them from copal wood, which made them tougher. Today, alebrijes are a key part of Mexican folk art and appear in annual parades. Their bold colors and detailed patterns make each piece one of a kind.

Talavera Pottery

Talavera, or talavera poblana, is tin-glazed earthenware from Puebla and Tlaxcala. It has roots in Talavera de la Reina, Spain, but Mexican makers formed a local style and turned Puebla into a major pottery center. Colonial churches needed tiles and clay work, and guilds set high standards.

Talavera blends methods from China, Italy, Spain, and native groups. It has an ivory base and often blue designs, along with pink, green, violet, yellow, black, and orange. You can see it in bowls, plates, and building tiles across Puebla. Many kitchens and facades still show these detailed works, showing their long-lasting appeal.

Black Clay (Barro Negro)

San Bartolo Coyotepec, Oaxaca, is home to Barro Negro, or black clay pottery. In 1950, artisan Rosa Real Mateo De Nieto found a way to give the clay a shiny black finish, replacing the older matte gray look.

Makers polish unfired pieces with a quartz stone before firing to get a smooth, metallic look. During firing, they close the kiln vents at a set time, reducing oxygen and turning the clay black instead of red-brown. The result looks like obsidian, often with carved designs. Many pieces are decorative, some are usable, and all reflect old methods with a fresh touch.

Tree of Life Sculptures

The Tree of Life, or Árbol de la Vida, is a colorful clay sculpture tied to Metepec in the State of Mexico. These multi-level works carry stories through many figures and symbols. During the colonial era, they helped teach Bible stories, often showing creation with Adam, Eve, angels, and a serpent.

Modern pieces now cover wider themes-daily life, history, and fantasy scenes-rising from a central trunk that stands for life and spirit. The fine details and strong colors turn each Tree of Life into a full scene crafted by a skilled storyteller.

Textiles: Sarapes, Shawls, and Mazahua Embroidery

Mexican textiles vary by region. A well-known example is the sarape from Saltillo, Coahuila: a rectangular, symmetric blanket with geometric designs and a central diamond or medallion. Woven of cotton or wool and dyed with natural pigments, sarapes offer warmth and a clear mark of Mexican identity. Since at least 1750, French threads like silk and metallic fibers also appeared in some designs.

The rebozo shawl grew after the Spanish conquest. For at least 500 years, women used it to cover their heads in temples, and it later became a symbol of Mexican womanhood, worn even by women in the Revolution. Santa María del Río, San Luis Potosí, known for Otomi weavers, is famous for fine rebozos. The Mazahua people in the State of Mexico make detailed embroidery in wool and cotton, with designs of plants, people, and animals, taught through generations. These textiles-blankets, bags, and clothing-are often sold by the makers themselves.

Silver Jewelry and Metalwork

Before Spain, metalworkers in Mesoamerica already shaped silver, gold, and copper. They inlaid gold in copper, hammered metal very thin, and cast with lost-wax methods for jewelry and ornaments. The Spanish added filigree, a lace-like effect using twisted threads of metal. At first, Indigenous makers could not work with precious metals, but the craft grew again later.

Taxco, Guerrero, is widely known as the “silver capital of the world.” Work there dates to 1593 and blends native and Spanish skills. Taxco silver often reaches 925 purity. Artisans make religious items, modern jewelry, accessories, mirrors, and statues. About 15,000 silver workers keep the trade strong and export widely. Copper work is also active, especially in Michoacán, where hammered vessels serve for cooking tasks. Santa Clara del Cobre hosts a copper festival every August.

Blown Glass and Glassware

Blown glass in Mexico has more than 500 years of practice, especially in Jalisco-Tonalá and Tlaquepaque. With simple tools like a hollow pipe and often recycled, lead-free glass, makers shape many useful and decorative items. The quick, precise steps draw many visitors who watch and buy.

Common pieces include drinking glasses with thick rims, small animals, and detailed decor. Bright colors and small, natural flaws give each piece its own character. Using recycled glass also reduces waste and gives new life to old material.

Leather Goods

Leatherwork ties closely to Mexico’s horse and charro (cowboy) culture. León, Guanajuato, calls itself “The Capital of Leather and Footwear,” showing long skill in this field. Makers produce saddles, belts, portfolios, wallets, jackets, hats, and many types of shoes.

Traditional leather often shows flowing designs made with punch-and-tool methods, then dyed or varnished. Leather also appears in furniture, like the seat covers of equipale chairs, and in lampshades. This work supplies useful goods and adds to the look and identity of places like Guanajuato.

Paper Crafts (Papel Picado and More)

Paper crafts go back to pre-Hispanic bark paper from mulberry and fig trees. Today, paper is still a favorite medium. Two well-known types are papel picado and paper flowers.

Papel picado means “chiseled paper.” It consists of cut-paper banners hung across streets and in homes for parties and holidays. Patterns can be simple shapes or complex scenes. You see them for Independence Day, Day of the Dead, and many saints’ days. Makers often cut many sheets at once with great skill. Paper flowers, often made with papier-mâché, fill festivals and altars, especially for Day of the Dead. These crafts use simple materials to make bright, joyful decor.

Cajitas de Olinalá and Lacquerware

Cajitas de Olinalá come from Olinalá, Guerrero, and follow a long lacquerware tradition. For over 150 years, makers have used aromatic linaloe wood to create household items, with small boxes being the best known. The wood gives a pleasant scent.

Making one box can take a long time, sometimes up to two years. After varnish, artists paint and then carefully carve the surface. Many add 24k gold leaf for extra shine. This work supports most families in Olinalá. Elsewhere, Mexican lacquerware-a pre-colonial craft-adds a glossy coat to trays, bowls, and animal figures. Some methods show Asian influence brought by the Manila galleons, showing Mexico’s role in global trade.

Where Are Notable Mexican Folk Crafts Produced?

Regions and Towns Renowned for Artisan Traditions

Many states and towns are known for special crafts. A few highlights are below.

| Region/Town | Main Crafts |

|---|---|

| Michoacán (Santa Clara del Cobre) | Copper work, handcrafted furniture |

| Puebla & Tlaxcala (Puebla City) | Talavera pottery and tiles |

| Oaxaca (San Bartolo Coyotepec, San Martín Tilcajete) | Barro Negro, alebrijes, textiles |

| Guerrero (Taxco, Olinalá) | Silver jewelry, lacquered boxes |

| State of Mexico (Metepec; Mazahua areas) | Tree of Life, embroidered textiles |

| Jalisco (Tonalá, Tlaquepaque) | Blown glass; Huichol art also nearby |

| Guanajuato (León, Majolica centers) | Leather goods, Majolica pottery |

| Nayarit | Huichol art |

Each place keeps its own methods and stories, and these crafts carry local history into the present.

How Regional Identity Shapes Mexican Craft Styles?

The look of Mexican folk crafts ties closely to place. Skills pass down within towns and families, and local culture and materials shape the result. This is not just about geography or resources; it reflects unique histories and Indigenous roots.

- Huichol art in Jalisco and Nayarit shows Huichol beliefs and symbols.

- Oaxaca’s Barro Negro depends on local clay and polishing methods valued by local taste.

- Yucatán’s hot weather led to finely woven hammocks from local fibers.

- Catrinas, from early 20th-century satire, grew into a national icon.

Each piece tells a story of its makers and community, carrying living tradition from one generation to the next.

How Do Folk Crafts Impact the Economy and Exports in Mexico?

Role of Folk Crafts in Local Economies

Folk crafts are a big and varied part of local economies. In many rural and Indigenous areas, making crafts is both income and way of life. Skills often pass through family teaching, keeping old methods active.

Craft markets draw locals and visitors, helping whole towns. Places like Taxco (silver) and Olinalá (lacquerware) rely on their specialties, with many people taking part in production. Domestic use and ceremonies still matter, but tourism and exports bring needed income and help keep traditions going.

Export Markets for Mexican Handicrafts

Mexican artesanía reaches buyers worldwide and supports tourism. There is no single giant exporter; instead, small businesses, co-ops, and private efforts lead the way. Foreign support can help: a co-op in Hidalgo received help from the Japanese embassy to ship goods to Japan. Masks from Axhiquihuixtla, Hidalgo, were sold in a New York gallery at much higher prices than at home.

Global demand can bring money back to makers, but fair pay is a constant issue. Mass-made copies compete with handmade work. Buyers can help by choosing real pieces and paying fair prices to the makers.

How Are Folk Craft Traditions Preserved and Passed Down?

Significance of Family Workshops and Artisan Communities

Family workshops and close-knit towns keep traditions alive. Children learn by watching and helping older relatives. They pick up tools, patterns, and meanings over time. This keeps skills and stories in daily use.

In places known for Mazahua textiles or Olinalá lacquer, the craft shapes local identity and economy. The workshop is a workplace, a school, and a storehouse of culture all at once.

Challenges and Threats to Traditional Craftsmanship

Traditional crafts face many problems today. Cheap copies, often imported, push prices down. Copies may look similar but lack the care, quality, and meaning of handmade pieces. Real artisans cannot match factory speed or cost.

Lower income makes it hard to buy good materials or try new designs. Many young people see little future in the trade, so skills can fade. Mid-20th-century tastes also shifted many buyers to mass goods for a time. The balance between keeping tradition and meeting today’s market is hard.

Modern Revitalization and Artisan Support Initiatives

Public and private groups now back folk crafts. The Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de la Artesanías (FONART), founded under President Luis Echeverría, and state Casas de Artesanías help makers produce and sell work.

Awards and events, such as the Premio Nacional de Arte Popular, bring attention. Banks and private groups, like those linked to Banamex, support artists and host shows. Art schools teach specific crafts, and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura runs a Crafts School. Some debate how much outside artists should shape designs, but these efforts help makers earn, try new ideas, and keep crafts active for the next generation.

How Can You Experience and Collect Folk Crafts of Mexico?

Visiting Artisan Markets and Museums

To get the full experience of Mexican folk crafts, visit artisan markets and museums. Mercados de artesanías are full of color and sound, and they let you meet makers, watch how they work, and buy straight from them. Oaxaca’s markets show textiles and pottery; Taxco’s shops focus on silver. These places are social centers as well as shopping spots.

Museums add background and history. The Museo de Arte Popular in Mexico City and regional museums in Michoacán and Puebla hold strong collections. Past shows like “Spirited Folk Arts of Mexico” (San Francisco International Airport) and “Folk Art of Mexico” (Mingei International) showed many types-from clay figures to alebrijes. Museums help you see the stories and meaning behind the objects.

Responsible Purchasing and Authenticity

Buying responsibly supports makers and keeps real traditions strong. Many copies flood the market. To make sure you get the real thing, buy directly from artisans, co-ops, or trusted stores that name the maker and place.

Signs of handmade work include:

- small variations from piece to piece,

- natural imperfections,

- traditional materials and dyes.

Talk with the artisan about the process and meaning. Your purchase then helps the person who made the item and keeps skills alive. Real Mexican folk art carries human touch, cultural memory, and creative power that factory goods cannot match.

Leave a comment