Mexican artisan culture is a bright, detailed tapestry built from centuries of history, many indigenous traditions, and European influence. It is more than pretty objects; it is a living expression of Mexico’s spirit and a core part of national identity. The term “artesanía,” popularized in the 20th century, marks the line between handmade goods using traditional methods and factory-made items. Each piece, useful or decorative, carries a story of heritage, community, and skill.

From busy markets full of colorful textiles to quiet workshops where old techniques are carefully kept, Mexican artisan work thrives. It shows the strength of its people, connects past and present, and stands as a strong symbol of pride. Its richness comes from diversity, with each region adding its own styles and materials to a shared artistic legacy.

How Do Crafts Reflect Mexico’s Identity?

Mexican crafts mirror the country’s layered identity. They form a wide group of objects made from many materials for daily use, decoration, and ritual. This comes from a blend of indigenous and European methods and designs, often called “mestizo.” After the Mexican Revolution, leaders and artists pushed this mix to build a clear national identity, moving away from a Europe-centered view.

Bold color is a key feature. In pre-Hispanic times, people painted pyramids, temples, murals, and sacred objects in ochre red, bright green, burnt orange, many yellows, and turquoise. Later contact with Europe and Asia added new hues while keeping strong saturation. Motifs also tell a story: geometric patterns tied to pre-Hispanic roots and nature themes common in both indigenous and European-influenced work. Artesanía is art and identity at once, linked to both national and indigenous pride, often shown in Mexican film and TV.

Regional Influences in Craft Traditions

Mexico’s varied land has shaped strong regional differences in craft. Each state, and often each town, has its own style, materials, and methods. Examples include:

- Michoacán: handmade furniture and abundant copper work; Santa Clara del Cobre hosts an annual copper festival.

- Puebla: home of Talavera pottery, a Majolica ceramic mixing Chinese, Arab, Spanish, and indigenous designs; used in kitchens and on buildings.

- Oaxaca: known for burnished black clay and textile dyes made the old way.

- Huichol (Wixárika) regions: famous for beadwork and yarn paintings inspired by spiritual visions.

- State of Mexico (Metepec): “Tree of Life” clay sculptures with rich storytelling.

These local styles show both the spread of craft across the map and the deep, place-based knowledge inside each tradition.

Origins and Historical Evolution of Mexican Artisan Culture

Mexican artisan roots reach deep into pre-Hispanic times, grew over thousands of years, and changed greatly after the Spanish arrived. This long history created a tradition that is both ancient and still growing, showing resilience and adaptation. The path of artesanía is one of exchange, conflict, and a unique blend that shapes Mexico today.

From the organized craft of the Aztecs to the planned rebuilding of crafts by leaders like Vasco de Quiroga, each period left a clear mark. Moving from indigenous mastery to colonial influence, and later to a post-revolution push for national identity through craft, we see a creative legacy that lasts.

Pre-Hispanic Artisan Roots

Before Spain, Mesoamerica had advanced craft centers. The Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacán, Toltec, and Aztec all supported strong artisan work. Weaving, wood carving, and pottery were part of daily life and ceremony. By the late pre-Conquest era, the Aztecs had absorbed craft traditions from Toltecs, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Maya.

Chroniclers described markets in Tenochtitlan full of textiles, feather art, gourd containers, and precious metal items. Records mention goods from maguey and a wide range of pottery. Artisans held high status. Metalworking with silver, gold, and copper was advanced, using gold inlay on copper, hammering metal to thin sheets, and the lost-wax casting method. Strong color from natural pigments set the tone for the bright look that still defines Mexican crafts.

Impact of Colonialism on Craft Traditions

The Spanish conquest in 1521 changed artisan life. Early on, indigenous artisans faced harsh treatment because their designs were tied to pre-Hispanic beliefs. Some crafts, like feather mosaics, faded away.

At the same time, Spain brought new tools and techniques. The potter’s wheel and glaze changed pottery. New trades such as saddlemaking took root, and local makers added indigenous designs. In Michoacán, Vasco de Quiroga helped rebuild and organize crafts, encouraging towns to specialize. Later, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla promoted crafts to help poorer groups, setting up brick and pottery works and teaching leather skills to build self-reliance. After independence, guilds ended, foreign goods arrived, and early industry grew, which led to a short dip in quality in areas like pottery.

Modern Transformations and Revivals

After the Revolution (1910-1920), Mexico saw a strong revival of folk art as part of building a national identity. Artists and public figures such as Dr. Atl, Adolfo Best Maugard, Diego Rivera, and Frida Kahlo lifted folk art into the center of culture. Kahlo’s use of indigenous dress linked identity and craft in a clear way.

Governments joined in. President Álvaro Obregón promoted crafts abroad and funded early public folk art collections. Big exhibitions in Mexico City and Los Angeles during the Independence centennial raised the profile of artesanía. Later, FONART and state Casas de Artesanías supported makers and their sales. Interest dipped mid-century as mass goods spread, but in recent decades academics, collectors, and tourism brought fresh attention. More artisans are now named and known, and some innovate in production, design, and marketing, keeping traditions alive and moving forward.

Major Types of Mexican Handicrafts

Mexico offers a huge range of crafts. Every type-practical or decorative-tells a story about local materials, history, and skills passed down over time. From a soft rebozo to the fine lines of an alebrije, these works give a direct link to Mexico’s creative heart.

Below are key categories that show the variety of materials and methods in Mexican craft.

| Type | Key Regions | Defining Features |

|---|---|---|

| Textiles | Oaxaca, Chiapas, Puebla, Veracruz | Back-strap and treadle looms, natural dyes, huipils, rebozos |

| Ceramics | Puebla, Oaxaca, Jalisco, Michoacán | Talavera, black clay, glazed and unglazed forms |

| Metalwork | Taxco (silver), Michoacán (copper) | Filigree, hammered copper, jewelry and vessels |

| Wood carving | Oaxaca, Michoacán | Alebrijes, furniture, religious figures |

| Glass & Jewelry | Jalisco, State of Mexico, Taxco | Blown glass, beadwork, silver pieces |

| Toys | Nationwide | Bulrush, wood, clay miniatures and playthings |

Textiles: From Huipils to Rebozos

Textiles have deep roots in Mexico, older than the Spanish conquest. Early weaving began with basketry and mats, using agave fibers and cotton, sometimes spun with feathers or animal hair for warmth. Many women still spin cotton or wool at home.

The Spanish brought the treadle loom, which made bigger cloth, but the back-strap loom tied to a post or tree is still common. Embroidery in bright colors often shared information about the wearer’s community, age, and marital status. Two key garments are the huipil (a loose tunic) and the rebozo (a versatile shawl). The rebozo grew from cultural mixing after the conquest and has been used for at least five centuries. While synthetic dyes are widespread, many makers-especially in Oaxaca-still use natural dyes, keeping deep, rich colors. Across Mexico, men, women, and children weave almost any fiber into useful items and art.

Ceramics and Pottery

Ceramics and pottery are among the oldest and most common crafts in Mexico. In Aztec times, pottery was a high art tied to the god Quetzalcoatl. Pre-Hispanic methods built vessels by coiling clay and then carefully scraping and shaping until smooth. Spain later brought the wheel and mineral glazes, changing production.

Puebla stands out for Talavera, a Majolica glaze style blending Chinese, Arab, Spanish, and indigenous patterns. These tiles and vessels are part of Puebla’s look and identity. Beyond Talavera, Mexico makes many types of ceramics: Oaxaca’s burnished blackware; everyday cookware; and decorative pieces that echo ancient forms. While factories make most tiles today, handmade unglazed pottery still thrives and keeps old shapes alive.

Metalwork and Silverware

Before Spain, metalworking with silver, gold, and copper was highly developed. Artisans used gold inlay on copper, hammered thin sheets, and used lost-wax casting. Much work focused on jewelry and ornaments.

The Spanish added filigree, weaving fine metal threads into jewelry. During colonial times, indigenous people were often barred from precious metals, but these designs later returned. Today, Taxco is the main center for silver, producing pieces that sell worldwide. Copper work is strong in Michoacán, where hammered copper vessels are still made for cooking tasks. Santa Clara del Cobre celebrates this work with a yearly festival.

Wood Carving and Alebrijes

Wood carving has a long history, from palace furniture to today’s alebrijes. The Spanish brought European furniture styles, often made by indigenous carvers, and techniques like parquetry arrived through trade with Asia.

Alebrijes show the playful side of carving. Pedro Linares López first created them in Mexico City in 1936 after dreaming of odd, mixed animals during an illness. He used cardboard at first. In San Martín Tilcajete, Oaxaca, makers later carved them from wood to make them sturdier. Each piece is unique and painted with bright, cheerful colors, mixing folk tradition with personal imagination.

Glasswork and Jewelry

Glasswork, introduced by the Spanish, developed local styles over time, often marked by bold colors and fun shapes. While newer than pottery or textiles, it adds to Mexico’s decorative arts, from useful items to ornaments.

Jewelry draws on precious metals, beads, and other materials. Beyond Taxco silver, artisans make many kinds of adornment. Huichol beadwork stands out: tiny beads pressed into wax or resin create patterns tied to Wixárika beliefs and symbols. Old metal skills mixed with added techniques and indigenous design sense make jewelry that feels both rooted and distinct.

Traditional Toys and Games

Traditional toys and games show creativity using simple materials. Many are small versions of daily objects or fantasy figures made from bulrush, wood, cloth, clay, and sometimes lead. These toys often came from humble settings and brought joy to children with limited means.

The art lies in making something special from almost nothing. Older toys now appeal to collectors, but since the 1950s, foreign mass-made toys have cut into local demand. Even so, these toys remain part of cultural memory, supported by museums and cultural programs.

Iconic Regional Art Forms in Mexico

Many regions are known for hallmark crafts passed down across generations. These pieces are more than goods; they are cultural markers people recognize and cherish. They reflect a mix of indigenous roots and colonial influence.

From the clean lines of Talavera to the spiritual imagery of Huichol art, these traditions offer a wide view of Mexico’s artistic heart for locals and visitors alike.

Talavera Poblana Pottery

Talavera from Puebla shows how local skill and European methods came together after the conquest. Puebla was one of the main pottery centers in the Americas, and Spanish techniques raised its profile even more.

Talavera features detailed designs, often in blue and white, but other colors appear too. It decorates bowls, plates, and jars, and it covers building facades across Puebla. Strict rules protect “authentic Talavera,” with quality and design standards that keep its name and legacy strong.

Black Clay from Oaxaca

Oaxaca’s black clay, or barro negro, is prized for its look and shine. In the 1950s, Rosa Real Mateo De Nieto from San Bartolo Coyotepec introduced polishing and low firing that brought out a glossy black surface without glaze.

Before this change, the clay looked matte and gray. The process polishes the damp piece with quartz stones, then fires it at a lower temperature, tightening the surface and making a deep black sheen. Items range from figurines and candelabras to useful vessels.

Huichol Beadwork and Yarn Paintings

From the Sierra Madre Occidental in Jalisco and Nayarit, Huichol (Wixárika) art is rich in meaning. Beadwork uses tiny beads pressed into beeswax or resin to show deities, sacred animals, and visions from peyote ceremonies. Yarn paintings (nierikas) press colorful yarn onto a waxed board to tell visual stories.

These works are sacred expressions, carrying history, beliefs, and identity through color and symbol. The tradition is old, and its look and depth continue to reach audiences everywhere.

The Tree of Life Sculptures

The “Tree of Life” (Árbol de la Vida) is a clay sculpture from Metepec, State of Mexico. These tall, layered pieces serve religious and decorative roles, full of figures and scenes painted in bright colors. The base often shows the shaping of life, and the whole piece tells a spiritual story.

Early versions showed biblical themes like the Garden of Eden. Over time, scenes grew to include daily life, Mexican history, and fantasy. Flowers, fruits, animals, and many small figures fill the work. Making one takes time and skill, and each piece is one of a kind.

Charro Hats and Traditional Attire

The Charro hat (sombrero de charro) is a leading Mexican craft and a strong symbol of identity. It arose from the mix of Spanish clothing and local use. Beyond sun protection, it once marked social rank.

Over time, the hat gained fine trims and materials, including hand embroidery with many colored threads. It became a blend of garment, accessory, and artwork with a very Mexican feel. Today it represents the charro, mariachi, and Mexico worldwide.

Making Process: What Goes Into Mexican Artisan Work?

Creating Mexican artisan work is more than making things. It follows tradition, respects materials, and often involves families and whole communities. Each step has purpose and history, and knowing the process helps people value each piece.

From choosing raw materials to applying long-taught techniques, every part of the work shows dedication and cultural continuity.

Material Sourcing and Preparation

A piece begins with finding and preparing raw materials. Artisans use local resources that reflect their region. For pottery, they locate clays, dig them, then clean and prepare them by sifting, grinding, and mixing to get the right texture. For textiles, they harvest cotton, wool, and agave fibers. Dyes once came mainly from plants and animals-cochineal gives deep reds, known since pre-Hispanic times. Many makers, especially in Oaxaca, still choose these labor-heavy natural methods to keep rich color.

Wood is selected based on the form needed, from sturdy furniture to alebrijes. Paper for crafts like banderolas may come from tree bark (mulberry or fig) and is washed, boiled with ashes, rinsed, beaten, and dried in the sun. This close knowledge of materials and how to prepare them gives each piece a strong link to the land.

Techniques Passed Through Generations

Skills move forward through teaching and practice within families and communities. Most artisans learn through apprenticeship-formal or informal-rather than in schools. This keeps time-tested methods alive while allowing careful change.

Potters still use coiling alongside the wheel. Metalworkers cast with lost-wax and also make filigree jewelry. Weavers work on back-strap and treadle looms, building complex patterns through years of practice. Alebrije makers teach both the original cardboard approach and later wood carving. Passing on this knowledge is not only about copying designs; it’s about the feel of the craft, the rhythm of making, and the meaning behind each stitch, cut, and brushstroke.

Collaboration Within Artisan Families

Craft work is often a family effort. Many artisans split tasks among relatives, each handling a part of the process. In weaving towns, some prepare and dye thread while others weave. In pottery, one person forms, another fires, and another paints.

This teamwork builds efficiency and keeps specialized skills inside the family. Groups like Loo’l Pich show how women share more than 20 embroidery techniques with younger people, protecting both heritage and livelihood. Working together strengthens bonds and keeps traditions active.

Cultural and Social Roles of Artisan Work

Mexican crafts carry cultural and social meaning beyond beauty and sales. They support spiritual life, bring people together, and keep memory alive. These objects are part of how communities live, celebrate, and remember.

From sacred rituals to public markets, craft links people to tradition and strengthens community ties.

Ceremonial and Religious Significance

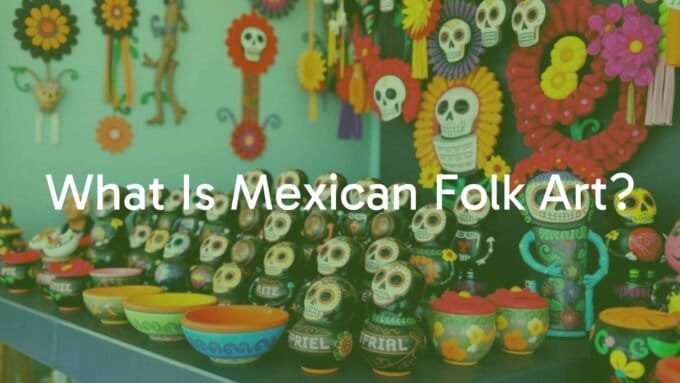

Artisan work is closely tied to faith and tradition. Many objects are made for saints’ days, holidays, and honoring ancestors. Día de los Muertos is a major moment for crafts, filling homes and altars with sugar skulls, skeleton figures, and flowers made from local materials. Some black pottery is made only for this time.

At Christmas, makers produce piñatas and detailed nativity scenes. For Palm Sunday, artisans weave fine palm crosses. During Holy Week, large papier-mâché figures of Judas burn in some places. Feasts often use cut-paper banners hung over streets and windows. These items are part of worship and help people connect with their beliefs and history.

Artisan Markets as Community Hubs

Markets are social centers as well as places to buy and sell. Weekly markets and permanent spaces let artisans present work, meet buyers, and keep traditions strong. Shoppers can find ceramics, textiles, metalwork, and wood carvings side by side.

For many families, these markets are the main source of income. They are also places to share news, tell stories, and teach culture. Visitors can meet makers, learn about materials and methods, and build respect for the work. Markets also show the range of regional styles, supporting a shared sense of Mexican heritage.

The Value of Mexican Artisan Culture Today

Today, Mexican artisan culture matters on many levels. It supports local economies and family incomes. It also carries history, identity, and memory, connecting people to old knowledge and craft.

The life stories of master artisans show the patience and strength it takes to keep traditions going in a fast-changing global scene.

Economic Importance for Local Communities

For many towns across Mexico, craft work is a key economic lifeline. People learn skills through apprenticeships and use them to make goods for daily life and special events. Most handmade products are used inside the country, from clothes and kitchen tools to ritual items, and sales support households and villages.

Public and private groups help. FONART and state Casas de Artesanías promote crafts and help artisans reach buyers and resources. Still, makers face competition from cheap mass goods and copies, which can lower prices. Even with hurdles, the craft economy supports self-reliance and keeps culture active through trade.

Personal Stories from Master Artisans

Each textile, pot, or alebrije carries the maker’s personal path. These masters hold knowledge passed down over time, and their stories show why artisan culture endures.

In Tlaquilpa, Veracruz, Nancy Carvajal makes wool garments. Taught by her grandmother, she brought back old techniques to create smaller pieces that still keep their spirit. In Cuetzalan, Puebla, Rufina Villa Hernández began embroidering at seven, now runs the Taselotzin hotel as a fair trade space, and founded the Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchikauanij group to support indigenous women. In Tamaletom, San Luis Potosí, Teenek artisan Cecilia Santiago Santiago started the Alabel Dhuche Collective to protect and promote Teenek culture through embroidery that keeps history alive. These makers are guardians, innovators, and leaders.

Role of Mexican Artisan Culture in the Global Marketplace

Mexican crafts reach audiences around the world. They act as cultural messengers, sharing design, color, and story. Global demand brings both chances and pressures for makers.

Exports grow, tourism feeds interest, and online sales open new doors. At the same time, artisans face tough competition and shifting buyer trends.

Export Trends and International Appreciation

Mexican artesanía has a steady place abroad. Tourists often visit Mexico for its culture, and many people seek real, handmade items with strong colors and patterns. Silver from Taxco is a major export and shows global demand for fine metalwork.

Sales beyond tourism are growing, especially online. While there is no single large exporter for all crafts, small firms and co-ops are making progress. A co-op in Hidalgo received funds from the Japanese embassy to sell in Japan. Ceremonial masks from Axhiquihuixtla, Hidalgo, once sold for low prices locally, later fetched much higher prices in a New York gallery. These cases show the potential if artisans can work through trade rules and meet market demand.

Challenges Facing Mexican Artisans in Global Markets

Many problems stand in the way. A major one is competition from factory-made goods and copies from abroad. These cheap products flood markets and undercut prices for real handmade work. Artisanal making also takes time, which makes price competition hard.

Tourists sometimes buy mass-made imitations rather than true handmade goods, which hurts both makers and cultural value. Some artisans lack access to good materials, fresh design ideas, or effective marketing, especially in poorer areas. Many makers stay anonymous, which can hold down prices. These pressures discourage some young people from learning the trade, risking long-term loss of traditions.

Maintaining and Safeguarding Mexican Artisan Traditions

Protecting Mexican artisan traditions matters for culture, history, and local economies. Keeping these practices alive takes joint work from governments, cultural groups, and artisans. The aim is to support living traditions while keeping authenticity and sustainability.

Several paths help protect this heritage, from funding and training to exhibitions and fair markets.

Programs and Policies for Preservation

Mexico has created programs to support crafts and makers. After the Revolution, leaders moved to formalize folk art support. President Adolfo López Mateos started a cooperative bank trust that later became FONART under Luis Echeverría. FONART plays a key role in funding, training, and marketing for artisans nationwide.

States run Casas de Artesanías-stores that sell handmade goods at fair prices and help buyers find authentic work. These groups also organize awards and events, including the Premio Nacional de Arte Popular, which honors excellence and motivates ongoing mastery. Such efforts address social and economic challenges so that traditions can pass to new generations.

Role of Museums and Cultural Institutions

Museums collect, protect, and display artisan work. In the early 20th century, scholars and artists built the first public folk art collections. Toluca opened the first museum dedicated to these arts in 1940, followed by the National Museum of Popular Arts and Industries. These places teach the public about history, methods, and meaning.

Shows in Mexico and abroad raise awareness. For example, “Spirited Folk Arts of Mexico,” using pieces from the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, ranged from simple toys to complex clay figures. By caring for and sharing these works, museums keep them safe and open for study, helping stories and skills reach the future.

Influence of Tourism on Craft Continuity

Tourism strongly affects craft survival. It offers a direct market and income for artisans and their communities. Many travelers come for culture and want to take home real pieces, which encourages makers to keep working and young people to learn.

But tourism can push fast, cheap souvenirs. Demand may lead to lower quality or imitations sold as handmade. Balancing income with authenticity is delicate. Responsible travel and informed buyers who seek real, fairly sourced goods help keep traditions steady and honest.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mexican Artisan Culture

What Are the Most Popular Mexican Handicrafts?

Popular crafts include:

- Ceramics and pottery: Talavera from Puebla and black clay from Oaxaca.

- Textiles: sarapes from Tlaxcala and Coahuila, rebozos, and embroidered huipils.

- Metalwork: silver jewelry from Taxco and hammered copper from Michoacán.

- Wood carving: brightly painted alebrijes, especially from Oaxaca.

- Huichol art: beadwork and yarn paintings with spiritual themes.

- Clay sculptures: “Tree of Life” pieces from Metepec.

- Leather goods and attire: charro hats and saddles.

These crafts are loved at home and abroad and reflect Mexico’s artistic heritage.

How Can Visitors Support Authentic Mexican Artisans?

Ways to help include:

- Buy directly from makers at local markets, co-ops, and workshops.

- Talk with artisans about materials and methods to better understand the work.

- Choose quality and authenticity over the lowest price; avoid cheap copies.

- Shop at state Casas de Artesanías or museum stores that back real artisans.

Thoughtful purchases support fair pay, protect culture, and help these living traditions continue for future generations.

Leave a comment